Reconstructing a History of Land Dispossession along the East African Coast

By Rene Odanga

I spent my summer in Nairobi and Mombasa doing pre-dissertation research on the practices of land dispossession that the British employed in creating the British East Africa Protectorate towards the end of the nineteenth century. My research took me to two sites, the Kenya National Archives Provincial Records Office in Mombasa, and the Freretown Descendants of Freed Slaves Community in Nyali, Mombasa.

KNA Provincial Records Office, Mombasa

During a previous research trip to the Kenya National Archives in Nairobi—the headquarters—archivists informed me that most of the documents that seemed pertinent to the questions I was asking, were not stored in the Nairobi Archives. The Nairobi Archives which most scholars of East Africa and Kenya use, largely keeps and preserves documents that are known to be in high circulation: these are typically files which are of most interest to researchers. Most other files are collected and held in records offices around the country. Most of the files I kept requesting in Nairobi on imperial advance, plunder, and dispossession of city states and sultanates—especially in relation to questions of land alienation, abolition, and labour—were in Mombasa.

In the years following abolition in East Africa (1907) the British attempted to sort out the squatter problem through techniques which were primarily supposed to legitimate their rule in the territory. Enslaved people and followers of rebellious leaders would be deported and resettled in different districts to scuttle the rebellion efforts of their former masters, the land and property of elite Africans and Arabs would be seized by the government and made public land (there is a strange case between 1907-1916 of Sheikh Mbaruk’s land in Mtwapa being used to build a Customs Office and generating much trouble when the Sheikh’s heirs return to claim it after his death. Mbaruk bin Rashid was a very influential coastal chief who led a rebellion against the British in 1895 that provided the opportunity for a lot of enslaved Africans to flee into the hinterland, significantly disrupting the coastal socio-economic system along the coast. Scholars have treated this rebellion as a slave rebellion, but Mbaruk was himself a notorious enslaver).1 This seizing and alienation of land is compounded by the colonial administration’s creation of land settlement schemes to settle various landless and land poor Africans affected by the politics of the time. [please add photo titled “File on the Acquisition of Sebe bin Mbaruk and Ayoub bin Mbaruk’s Land”]

As early as 1908, the British were creating smallholder land settlement schemes for Africans. Thus, state territorialization and political legitimation strategies through land allocation are not a preserve of postcolonial politics.2 And in Kenya Colony, especially outside of Central Kenya and the “White Highlands,” it certainly predates the years of “The Crisis” and the 1954 Swynnerton Plan—this stretches the problem of “land hunger” that became hotly contested in the years of the colony’s breakdown outside the settler factor.3

I consulted 12 files in the CA (Administrative Files) which are about governance and rule and the establishment of settlement schemes of squatters, freed slaves and public lands. And upwards of 15 files in CY (Land and Land Claims Files) mostly dealing with competing land claims between the Protectorate, Africans, Sultanates, the German East African Company, etc. [Add photo titled File Catalogue at Mombasa Provincial Records Office]

Working in the Mombasa Public Records Office was immensely difficult since there is no centralized cataloguing system and documents are stored in no logical order, and archivists routinely simply refused me access to documents claiming they were stored offsite, but immensely rewarding. Problematically, the referencing system does not align with that of the national archives, so upon return to Nairobi, cross-referencing was very complicated (documents filed under CA in Mombasa, might become AG or CP in Nairobi, documents under CY might become LND or take on wholly different referencing—or not be referenced at all).

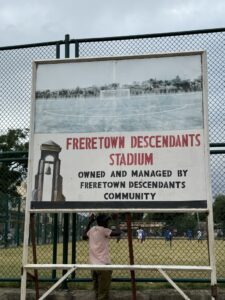

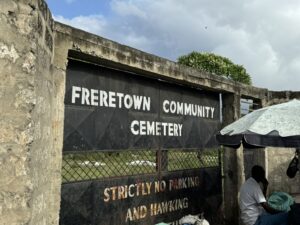

Freretown Descendants of Freed Slaves Community

In 1873, the Church Missionary Society started a settlement for African recaptives who had been rescued on the high seas by the British Navy and landed in Mombasa as part of the abolition effort.4 This community has existed in Mombasa throughout the age of colonialism on a settlement that was initially 600acres but has now shrunk to 50acres. After being freely introduced to the elders of the community, I had the opportunity to listen to their oral history accounts of their community’s origin, their claims to indigeneity/nativity in the area, and the history of their land’s dispossession. According to them, “their greatest oppressor” is the postcolonial government. It is after empire that they began to experience land insecurity and dispossession after independence—they felt more protected under imperial rule. They showed me what used to be their land, what remains of their burial grounds in the city cemetery, and records of their traditions (especially weddings). They insist that they have a valid claim to Kenyan citizenship and nativity because they predate both the Protectorate (1895), the Colony (1920) and the Republic (1963). “No one doubts that Kenyan Indians are Kenyan, yet they arrived with the railway in 1880. We were here before them, so of course we are Kenyan.”

They present an interesting aspect of study regarding the African experience under colonial rule because they present a different story of African response to colonial rule that is not simply collaboration or “beneficiaries” of European rule who were an African elite. The freed slaves of Freretown do not become colonial officials or askaris or so on. They are simply a group of Africans within the ambit of slavery and emancipation, colonialism, and decolonization who felt more protected under abolitionist British imperial rule.

They present an interesting aspect of study regarding the African experience under colonial rule because they present a different story of African response to colonial rule that is not simply collaboration or “beneficiaries” of European rule who were an African elite. The freed slaves of Freretown do not become colonial officials or askaris or so on. They are simply a group of Africans within the ambit of slavery and emancipation, colonialism, and decolonization who felt more protected under abolitionist British imperial rule.

I was freely allowed and encouraged to take a lot of pictures and conducted and recorded an informal 45-minute interview with an elder who urged me to return in future for further research.

This research trip significantly added to the shape of my research and opened up a whole new source base for my dissertation project and will go a long way in future research on dispossession in East Africa and the long history of economic inequality in African history.