Land Dispossession in Yorubaland, Nigeria

By Abiodun Ademiluwa

Last summer, between June and August, I was in Nigeria for archival research. I was intent on finding Yoruba Women and unearthing their role in the Atlantic slave trade and the Atlantic World at large. I also went into the archives to research the histories of inequality and dispossession, especially the gendered dimension. I visited the Lagos State Research and Archives Bureau (LASRAB) in Lagos, followed by the National Archives in Ibadan and the Kenneth Dike Library, located within the University of Ibadan. I was searching for women, but I found men first. They were everywhere in the archives! When I found women, they were mostly mentioned in passing and often nameless, revealing the inequality in archival documentation. Regardless, women, nameless or not, were present in the archives.

The Atlantic slave trade era was between the 15th and 19th centuries. Most of the documents available and/or that I had access to were from later periods. I was frustrated. However, to make the most of my time, I decided to check the available archival sources. While examining various documents, including newspapers, railway files, consular dispatches, missionary documents, correspondences, etc., I encountered women and men, land disputes, dispossession, and inequalities. I also found references to earlier periods in 20th-century documents. The documents I read show that land dispossession in Yorubaland has a long and gendered history from the precolonial to the colonial and post-colonial and that history is tied to slavery and colonialism.

The above document that I found in the National Archives, Ibadan, is an early 20th-century correspondence on the railway project of the British colonial administration. The letter dated June 10, 1907, from Sir Édouard Percy Cranwill Girouard, the High Commissioner of Northern Nigeria Protectorate to the governor of Southern Nigeria, is a follow-up on an earlier letter on the issue of compensating those who would be dispossessed of their lands and homes to build an extension of a railway line from Oshogbo to Ilorin. The line in Offa town in Ilorin would pass through three compounds, destroying homes and livelihoods and desecrating ancestral graves. Disregarding the plight of these people, Girouard believed that the “line should not be placed in a secondary position to the traditions of uneducated natives [even if] one is obliged to understand if not appreciate their dislike at the destruction of their compounds…” The suggested compensation was £10 per adult male and £5 per adult female. The case of the Oshogbo-Ilorin railway line extension reveals the dispossession of lands and properties in Yorubaland through colonial “modernizing” projects. The paltry compensation and the difference by half given to women also show how dispossession and gender inequalities are woven together.

The dispossession of lands is not the sole prerogative of the colonial government. Cases of land dispossession and disputes prevalent in the 19th and 20th centuries were part of the impact of the Atlantic slave trade on Yoruba communities. The findings of a study conducted in the early 1930s by H.L. Ward-Price, the Senior Resident of the Oyo province on Yoruba land tenure, highlight the vast population of a “slave class…descendants of slaves, who have no land of their own.” In this study, Ward-Price suggested that this landless class should be “given an opportunity to acquire their own holdings under a cautious system of freeing the family lands.” This statement begs the question, whose family lands or who were the owners of these lands? I found one of the people, a woman who had amassed large swaths of land in the 19th century through the Atlantic commerce.

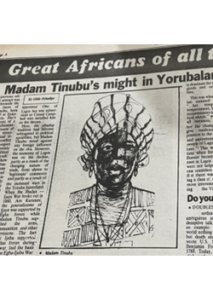

Madam Efunporoye Tinubu, c. 1807 – December 2, 1887, described as one of the “Great Africans of all time” in a 20th-century Lagos newspaper, was a prominent slave merchant in the 19th century. The “Petition of Right” to Tinubu’s estate filed by her relatives in the mid-20th century shows that Tinubu accumulated wealth from the trade in enslaved people. She also profited from the labor of enslaved persons on her coffee, kola nut, and palm oil plantations and owned large expanses of land and properties in the most desirable parts of Lagos and Abeokuta.

Together, these sources reveal the importance of land to wealth accumulation and the socio-economic and cultural life in Yorubaland. They also highlight the connection of land dispossession to the broader issues of slavery and colonialism. In sum, the Atlantic slave trade and European colonialism in Yorubaland contributed to the economic and gender inequality in the region

As I neared the end of my archival visit to Ibadan, I could see the shadows of the past lurking in this ancient and vibrant Yoruba city. The picture above was taken on August 9, 2024, around the bustling Challenge Road in Ibadan. This photo is of a fenced land with a sign on the gate that reads: “CAVEAT EMPTOR BUYER’S BEWARE THIS LAND IS NOT FOR SALE THIS IS A FAMILY LAND…” Notices like this are prevalent in the region, and one can hardly pass through a street without coming across at least one “caveat emptor” sign. This notice deterring potential land buyers (grabbers) serves as a reminder that the issue of land dispossession is very present in contemporary Yorubaland, Nigeria.